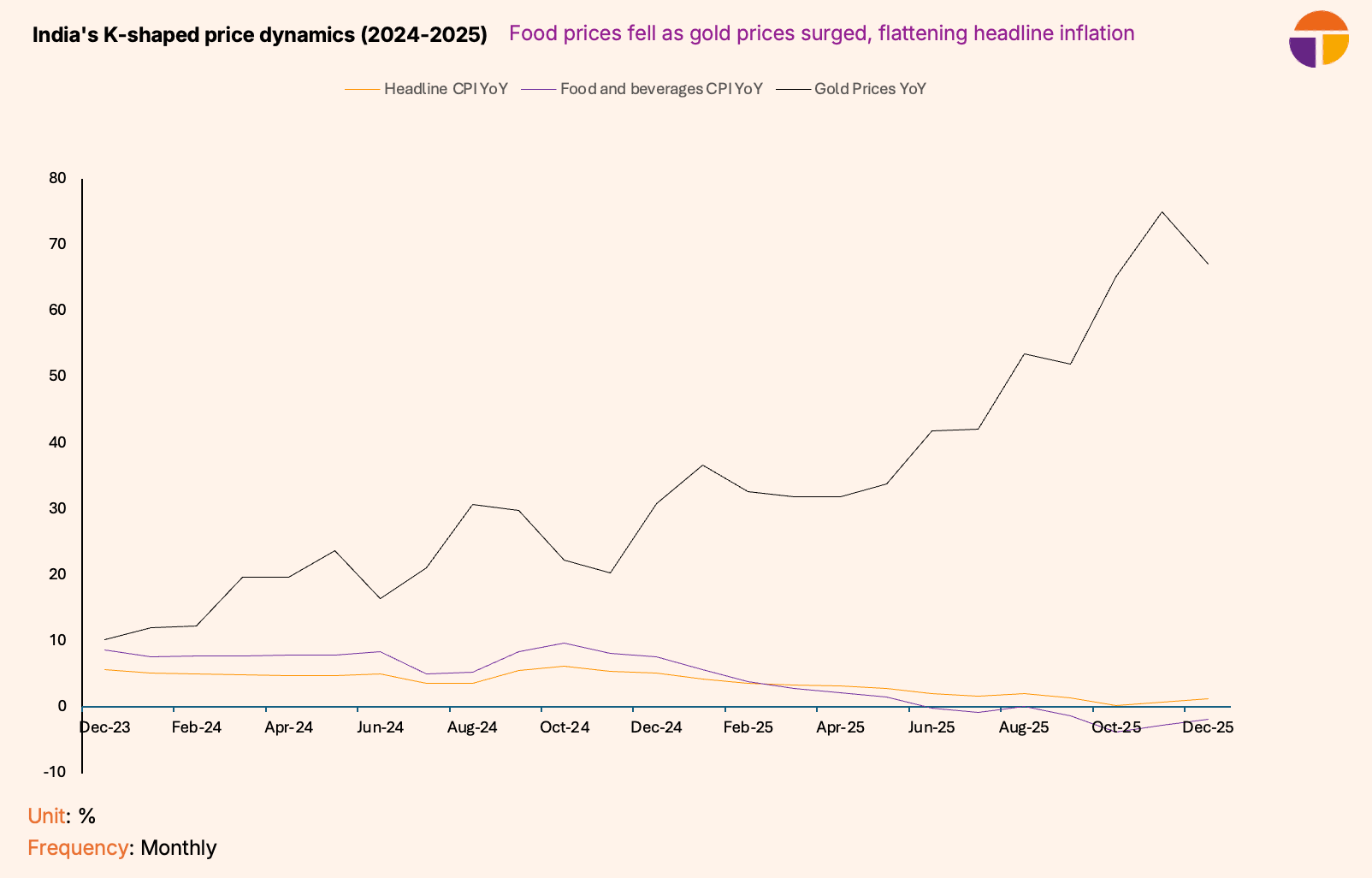

India’s inflation data for 2025 tells a deceptively calm story at first glance. Headline consumer price inflation fell to multi-year lows, spending much of the year even below the RBI’s 2% lower tolerance band. Beneath that flat headline sat a sharp divergence in price trends—one that split the inflation experience across households rather than easing it uniformly.

A closer look at CPI components reveals a distinctly K-shaped inflation pattern: food prices declined sharply even as asset-linked prices, particularly gold and silver, surged—creating one leg sloping downward and another sloping upward beneath a flattened headline. The result was a headline inflation print that masked two very different economic realities unfolding at the same time.

Gold prices shown are market prices (YoY) and not CPI sub-indices

Food deflation and the rural income paradox

Food and beverages CPI eased sharply from a peak of 9.69% in October 2024 to a low of -3.73% by October 2025. There is a base effect here, but even so the two-year food and beverages CPI is up only around 3% annually. With food and beverages accounting for around 46% of the CPI basket, this swing alone was large enough to pull headline inflation down from 6.21% to just 0.25% over the same period. By the end of 2025, as the base effect of the higher food inflation of 2024 waned, the trend began to reverse.

Food inflation swung from 9.69% in October 2024 into negative territory in 2025

For consumers, falling food prices offered immediate relief, boosting real purchasing power — particularly for lower-income households where food accounts for a large share of expenditure. Food prices are not just a cost; they are also income for rural India.

For agricultural producers, sustained food deflation compresses realised prices at the farm gate unless it is offset by higher volumes or procurement support. In practice, overall agricultural output has remained robust: total foodgrain production rose from about 332.3 million tons in 2023–24 to a record 357.7 million tons in 2024–25, reflecting strong crop performance, particularly in rice and wheat. Early estimates for the 2025–26 kharif season point to further gains, with foodgrain output expected at over 173 million tons from 169 million tons in 2024-25. Above-normal monsoon conditions and continued farm investment—reflected in record domestic tractor sales in 2025—have also supported rural activity.

In that sense, food deflation seems to be an outcome of a significant supply increase. This also means that the overall income in the agricultural economy probably went up as the quantity increase compensated for the price fall.

Gold, silver and the wealth effect

At the same time, prices of gold and silver surged sharply. Under India’s CPI framework, both are included in the “personal care and effects” category. While this sub-group accounts for about 3.89% of the total CPI basket, the specific weights of the precious metals are relatively small: gold at 0.53% and silver at 0.04%, or 0.57% combined. In 2025, the two precious metals recorded extraordinary year-on-year increases.

This rise tracked global asset-price dynamics—financial volatility, uncertainty, and the role of precious metals as stores of value. For households with exposure to gold and silver, the surge generated a wealth effect, improving balance sheets.

Despite its small weight in the CPI basket (≤ 0.6%), gold is a central part of India’s household balance sheet. According to a Morgan Stanley estimates, Indian households are estimated to collectively hold roughly 34,600 tons of gold, worth around USD 3.8 trillion—nearly as large as the entire country’s GDP—making India the world’s largest private gold holder.

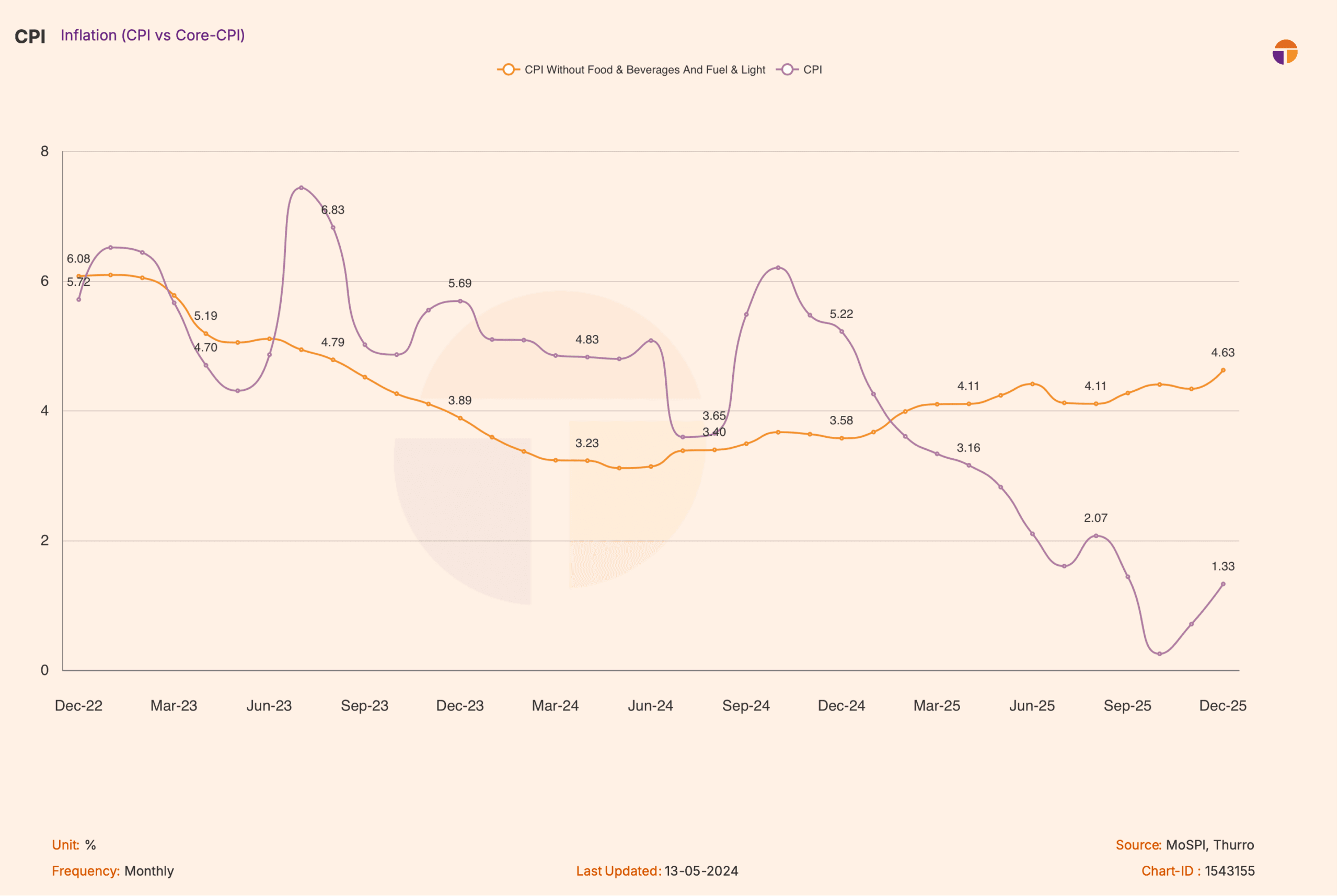

Why headline and core inflation became noisy signals

The coexistence of food deflation and precious-metal inflation distorted standard inflation metrics.

Headline CPI was pulled down almost mechanically by food prices. Core inflation, meanwhile, appeared to rise through 2025, ending the year at 4.63%—nearly a full percentage point higher than its January level of 3.67%.

Headline inflation fell sharply in 2025, closely mirroring the collapse in food inflation

Part of that firmness, however, reflected the presence of gold and silver rather than broad-based demand pressures. When precious metals are excluded, alternate “super-core” estimates remain close to and stable at the 2-3% range.

Super-core inflation hovered in the 2–3% range in 2025

The result was an inflation picture that looked calm in aggregate but dispersed underneath. Inflation showed up in the assets and not so much in the expenses.

Implications for policy and perception

This K-shaped inflation pattern complicates both policymaking and interpretation.

Low headline inflation created space for policy comfort, but persistent sub-2% prints also brought the RBI close to the lower bound of its inflation-targeting framework. Barring a marginal 2.07% print in August, headline CPI has remained below the 2% lower tolerance band since July 2025. While this does not yet amount to a formal failure under the RBI Act, it places the central bank close to a downside breach if sub-2% outcomes persist through the current quarter. Under Section 45ZN of the RBI Act, the RBI is required to submit a formal explanation to the government if inflation remains outside the 2–6% band for three consecutive quarters, outlining the reasons for the deviation, remedial actions, and the expected path back to target.

Such a development would not be unprecedented. In 2022, when inflation breached the upper tolerance limit of 6% for three consecutive quarters, the RBI prepared a statutory report to the government explaining the drivers behind the overshoot and its policy response. While that report was not made public, the episode underscored the accountability built into India’s inflation-targeting framework. A lower-band breach in 2026, should it materialise, would mark a rare inverse—reflecting not excess demand, but prolonged food-led disinflation amplified by index composition effects.

The widening divergence between food prices and asset prices meant households experienced inflation very differently depending on their income sources and balance sheets. For some, falling food prices eased day-to-day costs; for others, rising asset values reshaped wealth positions. The headline number flattened these differences, even as the underlying distributional effects became more pronounced.

It also marks a transition in India’s inflation framework. December is the final CPI reading under the 2012 base year, with the index set to shift to a new 2024 base from the January 2026 print. With a broader consumption basket and higher non-food weights, future inflation readings are likely to become less sensitive to food price swings and more reflective of underlying non-food cost pressures—bringing an end to the food-dominated inflation phase that defined 2025.

Cover photo credit: Unsplash

View disclaimer

This analysis draws on detailed Consumer Price Index (CPI) datasets available on Thurro Answers. Subscribers can access the full CPI series and run their own component-level analysis directly in the AltData section of the platform.

Unlock the power of alternative data

Do not just follow the market — stay ahead of it. Thurro helps you transform raw filings and alternative datasets into actionable insights.

Explore Thurro AltData Book a demo